Memory management is one of the most important tasks that an Operating System performs (after all, whatever other devices a system may support, it must have memory to work in). Understanding the operation of logical-to-physical address mapping and ensuring that memory is correctly allocated and released can be quite tricky. Any mistake here is going to lead almost instantly to a crash of the system; and a small, constant memory leak can soon gobble up free RAM.

The files include/memory.inc and include/memory.h define the memory map for IanOS, the former for inclusion in assembly files the latter in C files. It is important to ensure that these two files remain synchronized. All memory is allocated in 4K pages and the memory space is treated as a linear array of addresses from 0x0000000000000000 to 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF. At the risk of repeating the famous "640K" quote, you are unlikely to run into problems with available memory space!

Basic memory allocation is handled in the files mem32.c, ptab32.c, memory.c, and pagetab.c. The first two files deal with allocation of pages and creation of Page Tables whilst still in 32-bit mode (we need to be able to do this as we can't switch to 64-bit mode until paging is enabled, and we'll need some Page Tables to do this).

The use of Page Tables to map addresses to physical memory is central to 64-bit mode. When running in this mode virtual addressing is compulsory. Each address that is specified (the logical address) is mapped by the Page Table to a physical memory page. This means that the same logical address can refer to different physical addresses if different Page Tables are used. Also, it is possible for more than one logical address to refer to the same physical address. We make use of both of these capabilities.

Each process (task, whatever you like to call it) will have its own Page Table. The process's code will be located at UserCode and its data at UserData. It will also have a separate user stack and kernel stack (the stack used when the process is running kernel code) located at UserStack and KernelStack. The physical addresses will be different for each process. Because a process's Page Table will only contain entries for its own memory it cannot access memory belonging to another process. (The Page Table will also contain entries for the kernel memory, but this is only used by system calls.)

To understand the routines that create the Page Tables it is absolutely essential that you fully understand how paging works in 64-bit mode. Study section 5.3 of AMD2 (remembering that we are using 4K pages exclusively). I find that these routines are some of the most conceptually difficult in the system; a couple of months after writing them I had great difficult in understanding exactly what was going on (a sure sign that I didn't use enough comments - I hope that I have now remedied that).

Every Page Table also contains a set of entries that translate every physical addresses to a logical address. These follow the formula:

We need to do this so that when creating Page Tables, for example, we can access the underlying physical memory addresses. Entries in Page Tables are all physical addresses.

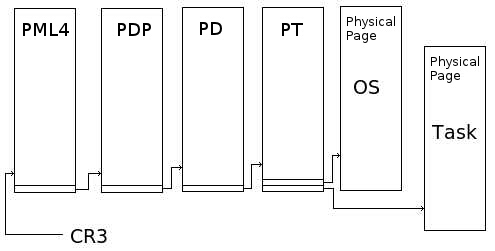

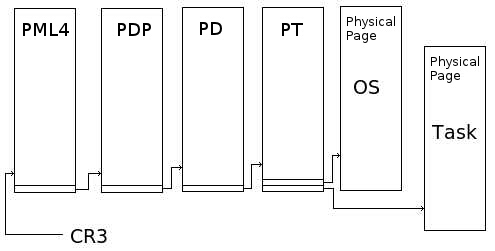

Page Tables consist of four hierarchical levels that link a logical address to a physical page. This makes it easier to create mappings in widely separated parts of the logical address space without having to specify loads of empty entries. The logical address is split into 5 parts (note that current implementations only support 48-bit addressing): 9 bits specify an entry in a top-level table (PLP4); these point to lower level tables (PDP). Entries in the PDP tables point to the next level of tables (PD); the next 9-bits then point to the final level tables (PT). The entries in PT tables point to physical memory pages. The final 12 bits (48 = 9 + 9 + 9 + 9 +12) then specify the offset of the address in the physical page. The register cr3 will point to the top level table.

The resulting Page Table looks something like:

The file ptab32.c contains the routine CreatePageDir which creates an initial Page Table whilst we are still in 32-bit mode. We need to do this as 64-bit mode won't work without paging enabled, and paging won't work without a Page Table. The structures used in this, and subsequent code, are really just aliases for 64-bit (long) integers and arrays of long integers. In the end this is all that the various table are. Note that we need to define alternate versions for 32- and 64-bit code; a long in 32-bit mode is only 32-bits. The function AllocPage32, which allocates physical memory pages in 32-bit mode is to be found in mem32.c. That file also contains the routine InitMemManagement which determines how much RAM the system has and sets up the array PMap[]. PMap[] is the record of which memory pages are allocated and which are free. The size of this array can't be set in advance, so I have just allocated a range of pages for it, in the kernel address space, well out of the way of other memory. (Remember, logical addresses are plentiful!) By the time we come to fill in the map it knows how big it is, so can allocate enough pages for itself.

AllocPage finds the first free space in PMap[], marks it as used, zero-fills the memory, and returns the address of the newly allocated page. The marking as used is done by setting the array element to the PID of the task that allocated it. This makes it very easy to ensure that all pages used by a task are returned to the system when the task has finished (more of this later).

CreatePageDir is fairly straightforward. At this stage we can address physical memory directly, so we just need to allocate pages for the table entries and construct the tables. Two further routines, CreateKernelPT and CreatePhysicalToVirtual, create tables for the kernel memory and the translation of all physical addresses to logical ones. The whole of this initial Page Table will be replicated in the page tables used by later tasks; they will also contain additional entries to allow them to address their own private pages for code, data, and stacks.

Creation of a Page Table for a new task is handled by the routine VCreatePageDir in pagetable.c. A page is allocated for the top level directory and its address is stored in pml4; this is the value that will be placed in register CR3 when the task is running. Next pages are allocated for the four PTs that will point to UserCode, UserData, UserStack, and KernelStack and these are stored in the appropriate PD(s). (Note that this assumes that these four areas of memory will be far enough apart to require separate PTs; it's easier that way.) We then create an entry in the PML4 table to point to the Logical-to-Physical map and a PD entry to point to the map of kernel addresses. Both of these items remain the same for all Page Tables and the entries are simply copied from the present Page Table.

Finally the routine returns the pointer to the Page Table.

You will notice that the macro VIRT, defined at the top of pagetable.c is used extensively in this and other routines. It is just a convenience that makes the code look a little cleaner; VIRT(type,name) gives the logical address corresponding to the physical address of the contents of name which is of type type *. We need this as all addresses in the various tables are physical addresses, which we cannot address directly. (The type specification is there to avoid compiler warning messages - I like to keep as many warnings as possible enabled as this helps to catch bugs.)

The function AllocPage64 allocates one page of memory, returning a pointer to the physical address of the page. After allocating a page a Page Table entry will be created for it by the function CreatePTE; this is called with the physical address of the page and the required virtual address as parameters, and returns the physical address. In most cases AllocPage is automatically called from the routines that create PT entries, but it is called separately in a few places.

The kernel and each separate task all have their own heaps to provide dynamic memory allocation. Memory on these heaps is managed by simple linked lists. Each memory block starts with a header (defined in kstructs.h) recording the size of the block, the address of the next block, and the PID of the process that "owns" the block. Memory is allocated by the function AllocMem. If there isn't a free block large enough to accommodate the request (plus the size of the header) then AllocMem automatically adds another page of memory to the heap; it returns the address of the newly allocated block. (I guess that I really ought to write in code to test for the possibility that no more memory pages are available.)

The function AllocKMem allocates memory on the kernel heap.

Memory is deallocated by the function DeallocMem which suffices for both user memory and kernel memory. Note that none of these functions will be called directly by user programs; system calls are provided which encapsulate these functions.

There is a potential problem in a multi-tasking system when allocating or deallocating resources. Should a task switch occur in the middle of the memory allocation routine and the task switched to then call the routine itself, we could end up in a heap (no pun intended) of trouble. The linked linsts would almost certainly get corrupted. We guard against this by setting a semaphore before entering these routines, and only releasing it once the allocation has succeeded. The x86_64 instruction set provides the cmpxchg which will test and optionally set a memory location as an atomic action which facilitates the use of semaphores.

You should note that I treat heap memory for a user program differently to many operating systems, where it is managed by the application itself. I provide system calls to manage malloc and freed calls. At the expense of a little efficiency, this makes the runtime code of user programs easier (and smaller) and makes it easier for the kernel to deal with allocation of new pages when the memory allocated to a process runs short. If you don't like this it would be easy enough to make the programs handle their own memory.